Letter 93 published 27 April 2018

THERE IS A DEMAND FOR THE TRADITIONAL MASS IN EVERY PARISH IN CHINA!

An interview with the

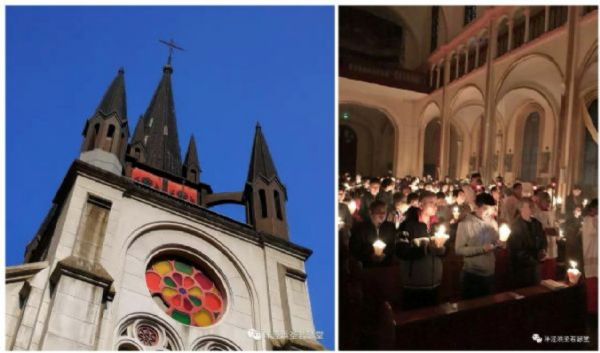

pastor of Saint Joseph’s church, Shanghai

This

week we present an exclusive testimonial. Thanks to one of our readers, to whom

heartfelt thanks are due, here is an interview with the pastor of Saint

Joseph’s parish in Shanghai. He offers the extraordinary form to his

parishioners, as the Sunday High Mass. This document is one of a kind: first

because it is the testimony of a priest in a country where the Church is under

tight surveillance; next because he is one of the very rare pastors of that

vast country to celebrate officially according to the terms of the motu proprio

Summorum Pontificum; lastly because

he speaks from one of the most inegalitarian and materialist cities on the

planet. This interview took place on April 7, 2018, Low Sunday. We invite all

of our readers to pray for this priest and for his community.

NOTE TO OUR READERS: Paix Liturgique is sending an envoy to

Asia May 14-22 to report on the traditional communities of Seoul, Taipei, Hong

Kong, and Singapore. Please do not hesitate to share any local contacts you

might have. We also welcome all contributions to pay for the expenses of this trip. The budget estimate is 2500 Euros.

1) In the West the Mass

in Latin has a complicated history: de facto prohibition in the 1970s when the

new Missal was promulgated; marginalization; then progressive renewal until the

present day when it occupies a significant position among the young as well as

in terms of vocations. Surely the situation in China has been very different:

would you tell us about the place of the Mass in its traditional form for the

past fifty years?

In China, the Mass in Latin concerns a tiny minority:

as far as I know it is celebrated in three venues in all of China: a parish in

south Peking, my parish in Shanghai, and in Wuhan (1) where, as I’ve discovered

on the internet, a priest is once again saying the traditional Mass. He’s a

52-year-old priest, like me. That is to say that like me he probably was

ordained about twenty-three ago, just before the introduction of the new Missal.

In China, the churches and seminaries that had been

closed in 1950 were reopened in 1978. There had been no change at the time in

the liturgy or in seminary teaching—everything picked up as before. The novus

ordo was introduced only in 1995, which is also when Latin and the old liturgy

stopped being taught in the seminary.

2) In the case of your

parish, how did you come to say the traditional Mass once a month and on feast

days?

The traditional Mass never stopped

being offered in my parish from 1982 to 2007, by the same priest. When he died in 2007 and I was named

pastor, I kept it up, always at my parishioners’ request.

3) If this is at the

request of your parishioners, why is it the case at Saint Joseph’s in Shanghai

and not elsewhere?

There is a demand for keeping the

traditional Mass on the part of parishioners in all the parishes! But since new priests didn’t have the

formation, choirs died out, Mass servers went away, and know-how was lost. This is a

very great shame, because nowadays those

most interested in the traditional Mass are the young. To be sure, they

need to put in an intellectual effort at the outset to understand the

traditional Mass. But once they’ve made that initial effort, they don’t want to

go back to the modern form in Chinese. Paradoxically, the same appetite is not

really to be found among younger priests: they are the most averse to the

traditional Mass. One of them, from my own seminary, recently told me that

“Latin did a great deal of harm to the Church”! Personally, on the other hand,

I feel that Latin connects me with the life of the Church universal.

This discrepancy between priests and the faithful

exists since 1995, ever since priests were taught to loosen up, to be cavalier.

It’s as if they must always show that they have freed themselves from

something. They scratch themselves, they move around while saying Mass ...

Also, 90% of my confreres in Shanghai no longer pray as a preparation for Mass.

One of them even regularly shows up at his church right after 7am, whereas the

Mass is scheduled for 7am. It seems to me that he can’t really have prepared

himself very well.

4) The Mass in Latin in

your parish is a particular case: it isn’t an alternative, it is the normal

parish Mass which, once a month, is said in the traditional form. What is your

parishioners’ reaction? Is it exactly the same people that you welcome to your

church on those Sundays?

No, it isn’t exactly

the same. Those who come to the traditional Mass are more numerous since they

come from all over Shanghai, whereas on other Sundays I only have the parishioners

of my territorial parish. Usually there are about 200 in the church on Sunday;

on Sundays when I celebrate the traditional Mass there are about 300.

5) As a priest and

pastor, what does this regular celebration of the older ordo do for you

personally? For example, does it influence the way you celebrate your Mass in

the new ordo?

When I celebrate the

modern form I keep the traditional form’s instructions in mind. You’d even be

surprised [laughs]: I wear the chasuble and biretta to celebrate the modern

form! You see, in the modern form everything is freed up, there are no rules. As

a priest, I am always concerned: “Did I in fact celebrate the Holy Sacrifice?

Did the miracle of Transubstantiation still take place? Haven’t I been

distracted? Haven’t I been lacking in faith?” In the old ordo, one needs only

to pour oneself into the mold and follow the rubrics, and I never have that

concern. This is a very personal thing, but the older order helps me keep the

faith, I never have any doubt about the reality and validity of the

consecration. The older order helps me be both fervent and rigorous. If I were

a professor in a seminary, I’d absolutely recommend celebrating the traditional

Mass to the seminarians. That’s what one of my old seminary professors, a Salesian,

did. Now he’s retired in Hong Kong. He’s a great friend of the traditional

Mass, he celebrates it often.

6) Do you see any

specific fruits in parish life?

First: every time, I

feel like I’ve done my duty. My Mass is said with fervor, it is never insipid.

Second: every time, I see new parishioners.

[He takes out his cell phone and looks over photos

he’s gleaned on the internet. The first one shows Pope Francis celebrating ad

orientem in the Sistine chapel. The second one shows a priest adoring the

Blessed Sacrament].

Third: you know, whenever people see a priest in this

posture, there are conversions!

7) Besides strictly

spiritual issues, do you sense a cultural struggle, from the point of view of

transmission, or of a kind of resistance against society around us?

I don’t particularly

feel like I’m transmitting a patrimony. True, my faith is “traditional.” That’s

how it is, I can’t teach catechism except in a “traditional” way. I teach the

“traditional” way of serving Mass, I wear my vestments the “traditional” way. I

can’t help it. I’ve been wearing the cassock every Sunday for the past

twenty-three years. I wear a white surplice to administer extreme unction (2),

which my confreres no longer do. I’d be quite incapable of doing otherwise. [He

pulls out his phone again and shows ordination photos of a young priest in an

Ecclesia Dei community]. And you know, when I happen upon these photos on the

internet, this young priest in Poland, I know that I am in full communion with

the universal Church. I no longer feel like I’m out of step, I feel like the

whole world supports me. [The interviewer is moved: he recognizes these photos

and remembers weeping when he first saw them. They are photos from the

ordination of Fr. Côme Rabany FSSP, taken as he was blessing his parents after

his ordination Mass]. As for being countercultural in a materialistic,

money-obsessed society . . . I don’t pay too much attention to that. As a

Catholic one oughtn’t take money as seriously as many Shanghainese do.

Generally speaking I’m not sure that the Catholic Church, particularly the

traditional Mass, holds much interest for the wealthy.

8) How did it go in practice? Did you

have to relearn Gregorian chant, or find long-lost old Missals? Did you still

have the right vestments? Did you compose new translations? Were there

liturgical adjustments?

Since there had been no

interruption in our parish, we had kept all the vestments and Missals. People

still knew how to sing in Gregorian. We had a good choir until 2007, which we

were able to revive. As for the ordo, we say the “pre-Revolution” Mass,

therefore as it was said before 1949. Actually I’ve kept all of my

predecessor’s books. For example, for August 15, we sing the old “Gaudeamus”

Introit, not the Mass promulgated

by Pius XII. Indeed, by the time the Assumption was proclaimed, the Mass was

already over in China!

9) Your church used to

be a French parish for several decades. Besides the architecture, what remains

of that presence?

Within the church there

remains a plaque in memory of Blanche de Montigny, the French first Consul’s

daughter; the iconoclasts overlooked it. All other traces of French influence

in the church were destroyed. As far as the community is concerned, it’s a

different story. It used to be said that Shanghai was an annex of the

Archdiocese of Paris on account of the great number and activity of French

missionaries here. We still have a few treasures left. [He pulls out a large,

framed black-and-white photo with a French title, “Shanghai plenary council,

1924.” In the photo there are many bishops, religious superiors, the apostolic

nuncio. His finger glides from one face to the other and he speaks of some of

them whose history he knows, pointing out the French figures . . .] The

Apostolic Nuncio went on to be a Cardinal . . . This

one died a martyr and is now canonized . . . That one was captured by the

Japanese, he was protecting his priests and was flayed to death . . . . Among

the French priests there are three that the community remembers vividly; I know

them only by their Chinese names. “Neng Mu De”: the revolutionaries kicked him

out but he wished to die on Chinese soil. He fell ill at the time of his

departure and his boat docked in Canton, where he died. “E Lao”: he had

inherited 100,000 Francs and used this inheritance to build a replica of the

Lourdes grotto in Pudong [a neighborhood in this megacity]. One of his French

nephews has already been to see us in Shanghai. “Xiao Jiazhu”: he taught chemistry

and had lost an arm (3).

10) The Church in China

is in a particular position, since the public authorities take an active

interest in it.

You have to take the

long view. For example, I’m thinking of the reign of Emperor Kan Xi

(1664-1723). Throughout China’s history the State has always had an opinion on

the Catholic Church. Whether it was harsh or benevolent, it never was

indifferent. Those who say nowadays that the State is indifferent to the Church

are wrong. In his day

Kan Xi looked into what might be good for him in the Catholic religion, and was

fearful of what might harm his power. That is why he always wanted Catholic

representatives around him, and public authorities have always had the same

concern: to insure that no harm should come to their earthly power. When I

celebrate the traditional Mass, I think to myself that I am exactly as in Kan

Xi’s day: I have the same faith, I celebrate the same sacrifice, and I have the

same problems to deal with.

-------

(1) Capital of Hubei

province in the middle of China; about 20 million inhabitants.

(2) There may have been an imprecision in the translation: did the priest mean his white surplice, or did he mean the white linen covering the sick bed?

(3) This third priest is easier to identify: it’s Jesuit Father Robert Jacquinot de Besange (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Jacquinot_de_Besange), a true hero whose personal activity saved no less than 300,000 people in the 1937 Sino-Japanese war. Note that the pastor of Saint Joseph’s is not native to Shanghai: his knowledge of his parish is therefore derived from his parishioners’ reports, from their memory and . . . from the communion of Saints.